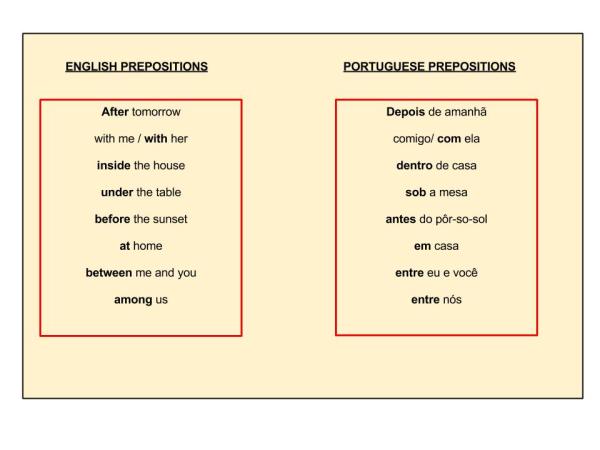

When we are learning a new language is common to be interested in how natives really speak, their common expressions, slangs and to learn them is always cool because make us feel a little bit less “gringos” and it also make brazilian people loves you even more 🙂 because we love when foreigners try to speak Portuguese ( <3)

When I was learning spanish in Colombia the popular slangs and expressions used to be my favorite words and I was trying to use them all the time, sometimes at the same time…hahaha (oops! =P). The truth is that by learning them I could understand easily what were people saying and it also helped me to interact. So today I brought you this small list of some popular brazilian expressions you should try to learn. 🙂 I bet you will be a much more popular gringo after you start to use them! 😉

“Legal”

It means “Cool.” But sometimes it can sounds like “ok”.

You’re gonna hear it a lot! It is one of the most useful slang words in the Portuguese language and you can use legal to describe almost everything you like.

Eg 1:

__Eu comprei um carro novo! (I’ve bought a new car!)

__ Sério? Que legal! (Really? That’s cool!)

Eg 2:

__O que você achou do meu amigo? (What did you think about my friend?)

__Ah, ele parece ser legal (Uh, he seems ok/nice)

Another slang to say something is “Muito legal”(really cool) is “SHOW DE BOLA“.

Eg 1:

__Esse lugar é show de bola!! (This place is really cool)

Eg 2:

__ Ontem nós nos divertimos muito. Foi show de bola! (Yesterday we had a lot of fun. It was really cool!)

We love soccer, so there are many slangs which came from this sport. So here we go with one more useful expression in case you are at a stadium:

Ei juiz! Cadê o penalty?

“Hey, ref! Where’s the penalty?”

When it happens to our soccer team, I think the ref is always blind. Don’t you agree with me? hehehe. Say it out loud(actually you should scream..hehe), to the TV, radio or when possible to the referee himself 🙂

É mesmo?? or “Sério?”

They mean “Really?” and it’s used in the same way we use “really” :), when you want to react to something unexpected or new fact or even, to be ironic.

Eg 1:

__Você sabia que a Português é Massa oferece aulas de Português via Skype? (Did you know that Português é Massa offers Portuguese lessons via Skype?)

__ É mesmo? Vou mandar um email para saber mais informaçoes. (Really? I’m gonna send an email to get more informations.)

Eg 2:

__Deus do céu! Esse vestido da Lady Gada está deslumbrante! (OMG! This Lady Gaga’s dress is gorgeous!)

__ Sério?! Eu nao acho. (Really? I don’t think so.)

Pra caramba!

Here’s a great expression to emphasize how off-the-charts something is. “Pra caramba” is most often used when you don’t want to simply say “muito” (very) and it usually comes in the end of the sencentes.

Eg 1: Essa cerveja é boa pra caramba! (This beer is great/amazing)

Cerveja gelada PRA CARAMBA!!

Eg 2: Eu gosto dela pra caramba! (I like her very much)

Fala sério!

It means “You’re kidding!” or “No way! Brazilians also say “Não acredito!”(I can’t believe it!) or “Mentiiiiiiiiira!” (It’s a lie – btw, I love this one!) to express the same feeling.

Eg 1:

__Eu acho que o Justin Bieber é o novo Michael Jackson. (I think Justin Bieber is the new Michael Jackson.)

__O quê??? Fala sério!! (What??? No way!/You’re kidding!)

Eg 2:

__Eu vou pedir demissao amanha e depois vou viajar pelo mundo. (I’m gonna quit my job tomorrow and after that, I’m gonna travel the world.)

__Mentiiiiiira!!! =O

Imagina!

You probably have already heard that brazilians are very hospitable. So when someone says “Obrigado” (you say it if you’re a man) or “Obrigada” (if you’re a woman), brazilians usually reply it saying “De nada” or “Imagina!”. It literally means “imagine!” but what we really want to say is “It’s no trouble at all!”, “It’s a pleasure for us to help you”.

Eg:

__Obrigada por nos ajudar. (Thank you for help us)

__Imagina! Foi um prazer. (It’s not trouble at all. It was a pleasure)

Com certeza!

This expression means “Definitly!” or more “Of course”. You cal also say it to agree with someone’s opinion.

Eg 1:

__Você vai pra festa mais tarde? (Are you going to the party, later?)

__Com certeza! (Definitly!)

Eg 2:

__Eu acho que as passagens de aviao deveriam ser mais baratas no Brasil (I think the flight tickets should be cheaper in Brasil.)

__Com certeza. Eles sao muito caros. (Definitly! They’re very expensive.)

Did you like it?? Sim or com certeza?? 🙂 🙂 So give us a “LIKE”, spread the good news, leave us your comments! Your opinion is very important to help us make this space better and better for you!

Beijos e até a próxima!